Jan 08 2010

Inside Obama’s Brain – Part 2

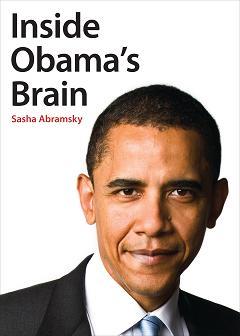

President Obama started 2010 with only a 50% job approval rating, down 18% from a year ago when he took office. More than three quarters of the non-white population still has a high opinion of him, compared to only 41% of whites. Similarly younger women are more likely to like what the president is doing at 58% compared to 55% of older men. One year ago, the nation was getting ready for a historic, unprecedented presidential inauguration, heady from the significant unity of purpose felt by the majority of Americans who cast their vote for Obama. But with the economy still shaky, a tumultuous debate over healthcare, the escalation of the Afghanistan war, and rigid battle lines drawn by Republicans, the honey moon seems to be over. Yesterday we spoke with freelance journalist and Demos Senior Fellow Sasha Abramsky, whose newest book Inside Obama’s Brain, attempts to learn who the President is, in order to determine where he is going. Today we bring you part 2 of our interview delving into the issues of the economy, war, and Obama’s future.

President Obama started 2010 with only a 50% job approval rating, down 18% from a year ago when he took office. More than three quarters of the non-white population still has a high opinion of him, compared to only 41% of whites. Similarly younger women are more likely to like what the president is doing at 58% compared to 55% of older men. One year ago, the nation was getting ready for a historic, unprecedented presidential inauguration, heady from the significant unity of purpose felt by the majority of Americans who cast their vote for Obama. But with the economy still shaky, a tumultuous debate over healthcare, the escalation of the Afghanistan war, and rigid battle lines drawn by Republicans, the honey moon seems to be over. Yesterday we spoke with freelance journalist and Demos Senior Fellow Sasha Abramsky, whose newest book Inside Obama’s Brain, attempts to learn who the President is, in order to determine where he is going. Today we bring you part 2 of our interview delving into the issues of the economy, war, and Obama’s future.

GUEST: Sasha Abramsky, freelance journalist and a Senior Fellow at Demos, author of many books including Inside Obama’s Brain

Find out more at www.sashaabramsky.com.

Rough Transcript:

Sonali Kolhatkar: So, given that you spent time writing this book and really trying to get inside Obama’s brain, in this first year in office relating to what we talked about earlier that he is someone who has this personal narrative, this background and he has a certain way of making decisions, is there anything in his first year in office that has surprised you, given that you’ve tried to get inside his brain? Has any action sort of made you think, well, that’s not in line with the psychological profile that I had painted of him?

Sasha Abramsky: Well, there are a couple issues where I’ve been disturbed by the direction that politics has taken, not necessarily surprised, but somewhat disturbed. I think there was an opportunity for broader, more wide-ranging reform of the banking system and I think that needed to be done. And there are a lot of advisors, not just on the left of the spectrum, but people like Paul Voelcker – very, you know, respected, historical figures in American politics and economics. And I think there was an opportunity that was missed. The second area is obviously health care reform and this one surprises me less and angers me more, in a way. But, I don’t blame Obama for it so much. Obama came into office determined that he wasn’t going to do what Bill Clinton did which was try and create health care reform through a series of commissions and boards without consulting Congress. And so he went overboard to make it a Congressional decision, to make it a Congressional action. And he brought all of the things that we talked about earlier – all of the desire for consensus, all of the desire to create as broad a bipartisan approach to the issue as possible. And then he left it to Congress. And the problem with that is that Congress is inherently (a) partisan, (b) a not very pleasant institution at the moment and (c) prone to stalemate and it has been for years and all of that is getting worse at the moment and at least in part it’s getting worse by an accident in numbers – the Democrats plus the two Independents have exactly 60 votes in the Senate, which gives them just enough power to break a filibuster if they’re all onboard and Republicans have just enough power to filibuster if they’re not. And I think we’ve seen this sort of degeneration into a series of games, a series of brinksmanship games where each and every Senator, just by accident of numbers, has veto power. So I look at that and I think, well, I don’t blame Obama for that because I don’t think that with all the goodwill in the world he could have necessarily twisted Joe Lieberman’s arm to get him to support a good health care reform, or Ben Nelson’s for that matter. But I do think it’s sad because I think there was this real sort of possibility for transformative change in health care and many other arenas. On the other hand, and I know this is a long answer to the question but, one of the things that increasingly fascinated me as I wrote my book was that I ended up telling two stories – one story was what was going on inside Obama’s head, how he approaches politics, how he approaches decision-making, but the other story was the interaction between Obama and his audience, the American electorate. And, the longer I researched the book, the more I thought, well, there was something very strange going on in 2008. There was this sort of utopian moment where millions of people had this tremendous passion for Obama the individual, and they’d give up their after-hours work time, they’d give up their weekends to campaign for Obama, if they had $50 to spare they’d put it in the Obama campaign, if they had a few hours where they could do tele-banking from their cellphones, they’d do it and there was this tremendous emotional sense – if we could just get Obama to November 4th, if we can just get him 270 electoral college votes, then come November 5th, everything will look different. And I think one of the things that surprised me in the last year is obviously things don’t look different overnight – change takes time, with the best will in the world change takes time and I think a lot of the people who supported Obama, they basically thought that everything that needed to be done had been done by November 4th and the stamina wasn’t there to really push Obama for change in the year since. And I think that’s one of the reasons that we’re seeing this sort of boomerang effect, this disillusionment effect is that a lot of the changes needed grassroots momentum, they needed people from below pushing Obama to make the changes and when that momentum didn’t stay, when it didn’t stay the course in ’09, I think a lot of people got quite cynical and quite suspicious of the political process. And that to me has been one of the sadder denouements of the last few months.

SK: I want to talk about economics. You mentioned earlier that, economically, Obama is quite conservative and in your book you talk about the way in which he does decision-making. At the same time that he’s intimately involved in the details, he does step back and tries to bring the best people, the best team together and delegates to them and he wants to be inclusive and he’s put together this economic team which we saw very early on in his presidency and they reflect quite a conservative free market ideology. Is he a free market ideologue?

SA: Um, I don’t think so. He definitely supports the tenets of capitalism. He’s certainly not a socialist, he’s certainly not a revolutionary, he’s certainly not somebody who wants to be the president shaking the pillars until they collapse. I think he’s, in a sense, I think the best way to describe him is how he describes himself in The New York Times magazine interview last Spring and he says I’m guided by only one principle when it comes to economic policy, ruthless pragmatism. And I think you see this time and again in his decision-making. He basically is experimenting. There are no ready answers because we’re in uncharted waters; there are no easy solutions because so many parts of the system began to fail all at once. And we’re seeing a series of experiments, some of which are stillborn, some of which are going to work with modifications and some of which will probably have some fairly profound long-term impacts. And the comparison I make – and I’ve made it in my book but I think the longer I watch him in action, the more I’m willing to make it – is with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And Roosevelt – I mean both presidents came in at a bad moment but Roosevelt was a little bit luckier timing-wise – he came in four years into a financial crisis. So, even without the New Deal, probably the cycle would have gradually turned the economy towards better times. Obama came in, literally, as the economy was tanking. So, even with the best policy solutions in the world, we were going to enter a period of cascading unemployment, cascading bank failures and so on. But the commonality is that Roosevelt came in fairly conservative economically, certainly more interested in maintaining the system than transforming it and events pushed him in a more radical direction. And so, about two or three years into his presidency, by 1935, you start seeing these dramatic institution-building efforts to create social security, to create unemployment insurance. And these are the legacies that three-quarters of a century later, when we think of the New Deal, when we think of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, we think of those institutions. And I look at Obama, and I look at the sort of experimental months that we’ve been through and I look at the tentative steps now towards banking regulation, towards health-care reform, towards changing the way we calculate unemployment insurance and so on and I think there’s at least the potential that events are doing for Obama what they did for Roosevelt – pushing him economically in a more radical direction, a more interventionist direction. And I think that’s what we’re probably going to see. But when we come to 2012 and the presidential election, my guess is we’re going to look back and we’re going to see two parts to the Obama presidency: we’re going to see the first part which is a series of experiments basically characterized by economic caution. And then we’re going to see the second part – my guess is there’ll be a second stimulus package based on job creation. My guess is there’ll be banking reform and we’ll start seeing an institution of building legacy being created.

SK: Well, that remains to be seen. Let’s talk about war. Let’s talk about Afghanistan. The Iraq War and ending that Iraq War was one of the most important aspects of Obama’s foreign policy and escalating the Afghanistan War was the other part but progressives seem caught off-guard, it seems, after Obama became President by that campaign promise which he has actually fulfilled. Where does Obama lie on the issue of war, do you think? I mean, would you compare him to Clinton, for example?

SA: No, I’d compare him more, I think again, to Roosevelt or maybe to John Kennedy. There’s been quite a lot of commentary on this in the last few months that if you’re looking for an ideological prism through which to view Obama’s foreign policies, probably liberal internationalism. He’s not an isolationist, he doesn’t want America to withdraw from its role in the world, he doesn’t regret the fact that America is a military superpower, an economic superpower, a political superpower but he’s somewhat cautious as to how the weight is thrown around. And I think that when you look at the Bush presidency, the Bush presidency had no sense of limits. It had no sense that there were circumstances in which raw might was just an idiotic way to do foreign policy and there was a sense of hubris surrounding almost every aspect of the Bush foreign policy, not just war or peace issues but, more generally, climate change policy, for example. This extraordinary situation where the President of the United States made it very, very clear that he was a climate change skeptic. On nuclear policy, that was another issue that we had this cold war arsenal which was pointing at Russia and they had this cold war arsenal pointing at us and instead of making meaningful moves toward nuclear disarmament, the Bush team basically had this idea that we’re going to go it alone, we’re going to make ourselves invulnerable through ever greater reliance on next-generation nuclear technology. And the Obama administration has the exact opposite view and they’ve made a foreign policy priority to move towards nuclear arms reduction and a stated goal of the Obama presidency, and obviously it goes different from reality, but a stated goal is eventual nuclear elimination, the elimination of nuclear weaponry. So, I think that when you’re looking at the Obama foreign policy, it’s more humble but it’s not afraid to use force when the analysis has been made by the President and by his advisors that force is necessary. Now, coming back to what you were saying about a lot of the progressive base, and I’m not sure it actually is his base – it seems to me his base was far broader than the progressive movement – but a lot of the progressive wing of American politics is deeply disillusioned with what he’s done on Afghanistan and the most obvious example is Michael Moore’s letter. The filmmaker writes an open letter to the President saying that in making the choice to expand the war in Afghanistan, he’s betraying the hopes of millions of young voters who flocked to him in the 2008 election. And, that might or might not be the case. It might be that millions of people are feeling disillusioned. But, if they are, I would argue that they only have themselves to blame for that because Obama’s been entirely consistent, going all the way back to 2002, when he makes this speech which subsequently becomes quite famous against the move toward war in Iraq. And he says he’s not against all wars, he’s against dumb wars. And he defines the move toward war in Iraq as a dumb war but he then says in the second part of the speech that he favors the intervention against Afghanistan and he gets booed from elements of the audience. But all the way back in 2002, he’s making that distinction. And if you go to the 2008 election campaign, Hillary Clinton runs these ads, you know – Who do you trust to deal with the three in the morning phone call? And, she’s trying to portray Obama as weak on terror and weak on foreign policy and Obama does a series of very, very forceful responses – and I don’t think it was political posturing, I think he genuinely believed this – he said, look, I want to expand America’s role in Afghanistan, and he then says, and I believe that an extension of that is the Pakistan tribal areas. He’s extremely clear on that. In fact, McCain, at one point says to him he was being too hawkish and he was signaling his foreign policy decisions in public, which you should never do, says McCain. So, it seems to me that if progressives or some progressives are disillusioned with Obama because of Afghanistan, they shouldn’t have voted for Obama in the first place because he was absolutely clear that if he was president, he was going to devote more resources to Afghanistan. And this seems to me sort of representative of what I was saying earlier which is that an awful lot of people wanted to see an Obama whatever their dreams and hopes and expectations were and they didn’t necessarily read all the fine print that came with his candidacy.

SK: And, I remember Noam Chomsky being very clear about that. In fact, during the campaign and right after Obama won, he said several times that he was worried about the fact that many people were putting their hopes on Obama, that he became this blank slate for people to scribble their dreams on. I want to ask you briefly about the Republican critique of Obama given your research into where Obama’s coming from, some of his background in community organizing in Chicago, the church that he went to, the background that he has that’s so different from the established background and what he has done so far in his presidency in this past year. Were Republicans in any way right to be – from a Republican extreme conservative perspective – right to be petrified of him as they seem to be?

SA: I think what made the Republicans so scared of Obama was his ability to bring people into a movement, his ability to, in a sense, cut through all of the traditional political chatter and to bring into the political scene people who had never voted before or people who hadn’t voted for decades because they’d grown disillusioned. And I think that that’s where the transformative potential lies. It’s not specific policies. And when you actually talk to his community organizing mentors, a lot of them said to me, what’s most important about the kind of community organizing that Obama specialized in is what they call “relational organizing”. And, one man in particular, a man called Jim Caprero, who was a friend of Obama’s in Chicago, he said to me, look, issues come and go – issues make up headlines of the moment but a year or two hence you generally forget issues, individual issues. But the thing that remains is the ability to bring a bunch of people together around a set of ideals, around a set of broad, big picture ideals for change. And that’s the relational organizing that Obama learned in Chicago and it’s the relational organizing that Obama brought to his political candidacy and he did it very, very effectively. And I have an anecdote in my book: during the Iowa caucuses, he meets with some of the community organizing leaders from Chicago and other parts of the Midwest – it’s a private meeting – and he has this little conversation with Greg Galoutzo, who’s one of his mentors. And he says, Greg, all over the country, people are asking me, where did I get the ability to bring in money like I do, where did I get the ability to mobilize people politically like I do. And then Obama laughs and he says, I tell them the Gamaliel Foundation in Chicago, Illinois. The Gamaliel Foundation was this very regimented, disciplined organizing school that Obama went through when he was training to be an organizer. And I think that’s what the Republicans were fearful of, that here was a candidate who had the ability to bring people together in these relational nexuses and he had the ability to make people feel empowered. And even if individual specific policies didn’t end up being quite as radical as the Republicans thought they might be or feared they might be, at the end of the day the Republican Party functions best when fewer people are voting. And that’s something I’ve written about in my previous book, that when a segment of the population feels so disempowered that they withdraw from the political process, usually that benefits the Republican Party. And they’ve made that a key part of their strategy in recent years – limiting the electorate, making politics a game for elites. And Obama, in breaking that mold, in making people feel empowered, in bringing people to the conversation who’d always felt ignored – that, in and of itself, represented a huge threat to the Republican way of doing business and I think they were right to be scared of that.

SK: Does he face, finally, does he face the risk of – because he has become, you know, so much to so many people and cannot please everybody all at once – does he face the risk of leaving behind a legacy of bitterness and disappointment and disempowerment ultimately?

SA: Well, I had a conversation with a cultural historian called Troy Duster about this very fact. And he said, well look, at the moment we’re in a period of “illusionment” – and this was just after the election when Obama had sky-high approval ratings – but he said the flip side of “illusionment” is disillusionment. And I think what you see with Obama is the expectations were outlandish. That, even if he was the most successful president in American history, he still wouldn’t meet the expectations from the Autumn campaign, that people basically had almost deified him. We’d come closer to deifying him than we had to deifying any living politician. The only comparison in the last 50 years would be to John Kennedy. And I think the danger of that is that – well, there are two dangers – one of them is that you put expectations on people that can’t be met and the second one is that you make criticism impossible because nobody criticizes God. So, if Obama is a God, you can’t criticize him and politics stagnates. And I’ve argued in the Huffington Post and in other outlets in the last few months that the rise in criticism is as healthy a phenomenon as we could get because it means we’re no longer regarding our political leader as a deity. We’re regarding him as a mortal, as a skilled politician, but nevertheless as just a politician. And I think that’s good because no matter how different Obama is, no matter how skilled he is at talking the talk or even walking the walk, it’s healthy in a democracy for leaders to be held accountable. What’s not so healthy is if holding Obama accountable flips into profound disillusionment and cynicism and people walk away from the political process and I think that’s a risk – that we might end up with a situation where Obama gets millions of people to vote for the first time in 2008 and then in 2012 it’s just another election as usual. And he might well win reelection but it would be on a much smaller participation base and I think that would be a very sad, sort of second chapter to the Obama story.

SK: Sasha Abramsky, thanks so much for joining us.

SA: My pleasure.

SK: Sasha Abramsky is a freelance journalist and a Senior Fellow at Demos, author of many books. His latest, that we’ve just been discussing, is Inside Obama’s Brain. This was part 2 of our 2-part interview. You can hear the other part at our website: KPFK.org/uprising Find out more at Sasha’s website: www.SashaAbramsky.com

Special thanks to Julie Svendsen for transcribing this interview

Comments Off on Inside Obama’s Brain – Part 2